Cienega Seca Creek Trail Hike - July 26 2005

Part 2 - Rocks

|

I have only recently become interested in identifying rocks. Rocks

are a relatively permanent (within the scale of human longevity) record

of landscape

formation. To know the local geology is to better understand why certain

vegetation communities are present (or absent).I want to share with

you my fascination with the rocks and minerals I came across in the

mostly-dry wash of Cienega Seca Creek. Please note that some of these

identifications are tentative.

This Cienega Seca arroyo is an excellent location to rockhound. All

of the immediate geology ends up down here via gravity. |

|

| |

| The trail that accesses the arroyo from campus (where I live) is

termed Magohany Maze. I felt like a giant zigzagging through the

Curl-Leaf Mountain Mahogany. This footpath is quite overgrown and

provides great examples of Sierra Juniper, White Fir and Jeffrey Pine

seedlings. Along this path I continuously expected to encounter

Gold-Rush mining relicts, but didn’t. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Let’s begin with metamorphic rocks.

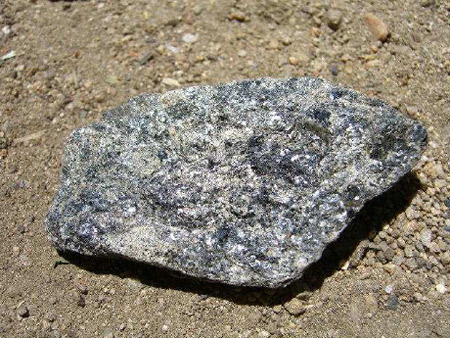

This Schist seems to be mostly Biotite Mica. Mica is formed when oxygen,

silicon and aluminum atoms are alternately heated and compressed.

Biotite Mica

contains iron and magnesium impurities that account for its dark color.

I will grind the small piece into a pendant eventually. Most micas can

be ground and used as mineral paints. |

|

| |

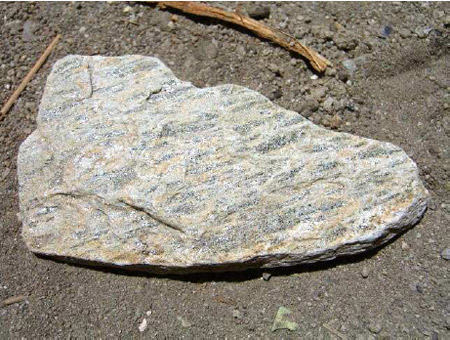

| Another example of Biotite Mica Schist. I have read that schist is

(or can be) low-grade metamorphosed granite in this area. The thin

sheets of black biotite mica precipitate out of the parent granite under

heat and pressure. When I say “low-grade”, I mean that this rock has

endured lower temperatures and pressures than, say, gniess. But we’ll

get to gneiss soon. |

|

| |

| This may be Chlorite Schist. Lovely green coloration... |

|

| |

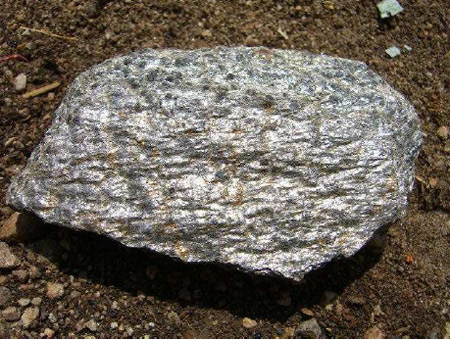

| These two specimens appear to be Muscovite Mica Schist. Muscovite

Mica is shiny and mirror-like. In fact, one can find larger pieces of

muscovite mica in the southern end of the San Bernardino

mountains—Mountain Center, Anza, Hemet area. It is said that old-timey

prospectors used to use large mica sheets as shaving mirrors. |

|

|

| |

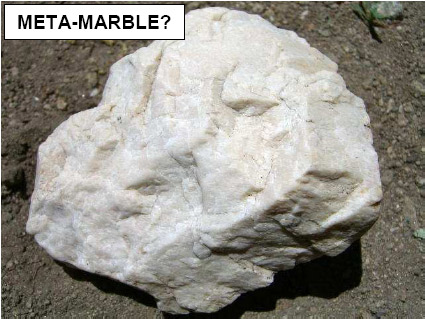

On to the Quartzites! Quartzite is metamorphosed sand. Sometimes

trace elements (or impurities, but I think this term has negative

connotations) get

squeezed out into bands. I would call this specimen Banded Quartzite. |

|

| |

| Another Banded Quartzite. I would also call this Rainbow Quartzite. |

|

| |

| I think this is Gray Quartzite. |

|

| |

| Pink Quartzite |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| And here we come to Igneous Rocks. A Feldspar crystal embedded in

quartz. The crusty band on top of this specimen is a pegmatite. Around

60% of the earth’s crust is feldspar. Pink feldspar is very

erosion-resistant. I would call this a Contact Rock—where two or more

rocks, and their distinct boundaries, are present. In this case,

pegmatite meets quartz. But in a more holistic, or largerscale view, one

could consider this specimen to be wholly a pegmatite. See how much I

don’t know? |

|

| |

| Again, this is either a Quartz/Feldspar Contact Rock, or a piece of

a much larger, large-grained Pegmatite. |

|

| |

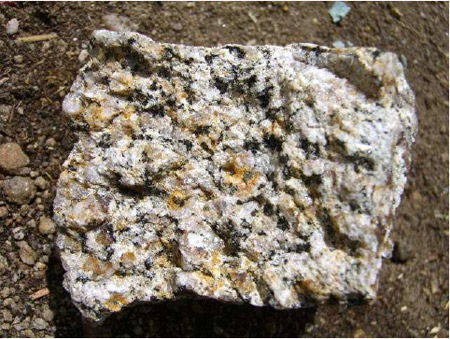

More Feldspar crystals.

These four pictures are examples of Pegmatites. These are just

large-grained granites. When a volcano dies, the underground magma

eventually cools off. The longer this process takes, the more time

crystals of quartz, feldspar, and mica have to grow larger. In fact, the

tiny red crystals in these photos are Garnets, which tend to form at

high temperatures. I love finding garnets. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Okay, I didn’t find this Pelona Schist here. But I include it

because of the blackened (burned) garnets that it contains (the black

dots). This comes from the San Gabriel mountains in the town of

Wrightwood. I have also found garnet-laden schist in Gladwyne and Bryn

Mawr, Pennsylvania. |

|

| |

| Another Contact Rock. This pegmatite has a chunk of Gneiss attached

to the top of it. Gneiss is metamorphosed granite. |

|

| |

| I think the following six photos are of Gneiss as well. Paragneiss

is metamorphosed sedimentary rock, while Orthogneiss is metamorphosed

igneous rock. The first photo may be Augen Gneiss, which is California’s

oldest rock at 1.7 billion years old. |

|

| |

| Our local Granite appears to be Quartz Monzonite. |

|

| |

| Sometimes that Chlorite Schist sports rusty Iron Oxide stains. |

|

| |

| What a cool rock! The green rock mineral is Epidote. The white

mineral is quartz. The orange crystals are Grossular Garnets. |

|

| |

| Where the arroyo crosses the trail that takes me back up to campus,

there are a few neat little encampments... |

|

| |

| I’m afraid that Mr. Bunny doesn’t care much for geology. But he does

like to chase the ground squirrels into their burrows! |

|

| |