Boiling With Hot Stones

|

From microwaving popcorn to roasting potatoes around a car’s hot exhaust

pipe, humans have developed a variety of cooking methods by which we

render food safer, more digestible, and more palatable. Stone-boiling is

one of my favorite Stone Age (pardon the pun) methods. Some alternatives

for boiling food are energy intensive and more difficult to prepare

(rawhide bags, pottery). Stone boiling requires a fire, some rocks, and

a coal-burned container.

I started experimenting with stone-boiling while living in Olympic

National Park (WA State). I had heard that some types of rocks were

better to use than others, but I couldn’t locate any information

regarding which tended to crack (or explode!) and which are keepers for

a lifetime. So here are the results of my very limited exploration on

the subject at hand.Let’s begin with the contestants.

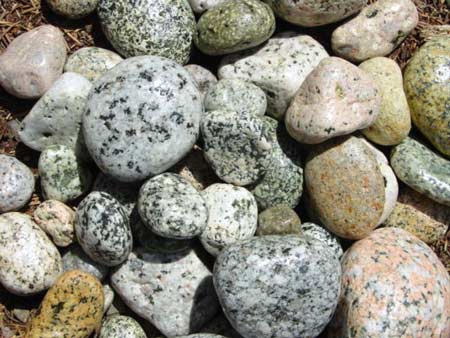

From the nearest extinct volcanic pluton, let’s welcome Granite!

Granite is relatively large-grained, which we think doesn’t bode

well for this igneous rock. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Although most of this melange of cobbles started out as lowly

depositional sand, these glassy rocks endured sweltering heat and

enormous pressures in order to metamorphose into the beautiful

Quartzites you see before you today! On a more serious note, there is

some Quartz and other igneous rocks in here as well. |

|

| |

And coming all the way from the spreading Pacific Oceanic Ridge,

taking 200 million years to get here, itís Basalt! Fine-grained basalt

has a good reputation for withstanding rapid heating and cooling amongst

abos in the field.

Good luck to all of you! |

|

| |

Ahem. Now that I have that out of my system...

Heating up the rocks... |

|

| |

| Got my coal-burned Western Red Cedar cooking vessel ready, in which

Iíll test the hot rocks. |

|

| |

| Wooden tongs are quite useful in handling the heated stones. Notice

the steam escaping from the bottom of the rock as it hits the lake. |

|

| |

| Rocks relaxing in the ďhot tub.Ē I subjected all rocks to at least

five hot immersions (unless they broke before the fifth trial). Which

will survive...which will crack under pressure? P. S.óI love those

tongs. Made from Yellow Cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis)...lightweight,

easy-to-carve...just the right width to afford a strong purchase on it

when handling an awkwardly-shaped rock. |

|

| |

| Poor granite. This species suffered a near 100% failure rate. Iíve

been told by a geology professor that water can infiltrate the

interstitial spaces between the relatively-large quartz, feldspar and

mica crystals and expand the rock when heated. To itís credit, granite

never sent shrapnel flying when it cracked. |

|

| |

| Quartzite fared a little better, being smaller-grained and more

homogenous throughout itís structure. About 50% of these survived. I

will note that when quartzite cracked, it sometimes exploded (but shards

never traveled more than a foot or so away from the wooden bowl. |

|

| |

|

| |

And the winner is...

Basalt out-performed the other species of rock by far. And yes--this

photo (used twice in this article) is of the basalt rocks post-fired.

Only about 5% of these cracked with use.

A few years later, I still use these particular pieces of basalt. They

show no signs of giving out. Incidentally, one can purchase smooth

basalt cobbles in fancy home/yard furnishing stores. |

|

| |

| After I get established in the San Gabriel Mountains of southern

California this Fall, I look forward to testing the various

rocksógneiss, schist, talc, actinolite, pure quartz, feldspar,

marble--found there. Iíll let you know how they work out.... |

| |

| View this article as a PDF |