|

Back to the Pleistocene! (To Save the Earth)

|

This article was published in Vigilance and Backwoodsman Magazine

last year. I definitely want to expand it someday soon...

Thirteen feet of rain fall yearly on the coast of western Washington, of

which seven inches have hit the ground since yesterday noon. For a week

I’ve been living on berries, mushrooms, foliage, roots and invertebrates

within the temperate rainforests and beaches of the Olympic Peninsula.

I am hunkered within the burned-out, yet living shell of an ancient

western red cedar, trying to start a campfire. Angry rivulets of aqua

pura cascade confusingly over the fire-scarred, exposed sapwood of this

millennium--old forest sentinel, rivulets that seem intent on thwarting

my efforts at coaxing the fire-spirit from this hand drill set. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| I’ve been carrying these firesticks--a long, straight branch from an

elderberry shrub (the spindle) and a short length of root (the

hearthboard) that I collected from a blown-over western

hemlock—underneath my clothing in an effort to dry them out. Strong

gusts from the west shower the area with sitka spruce cones. It’s

getting dark. I need a fire. If you’ve seen the movie Castaway, you

may remember that Tom Hanks attempted to make fire by two methods. The

first involved rotating a slim spindle of wood onto (and into) a wider,

flatter piece of wood. As friction increases at the contact point

between the two sticks, the woods disintegrate into a fine powder that

will spontaneously combust when the combination of downward pressure and

speed (applied wholly by your own two hands!) raises the temperature of

your efforts to approximately 800-degrees F. The resulting fire-egg

(a.k.a. coal, ember) would subsequently hatch into flames when applied

to a tinder nest of cattail seed head fluff, moss, slivers of wood and

shredded bark.

Humans and their kin have been using fire for at least 1.5 million

years, but for only one one-hundredth of that period of time have we

been able to actually create fire, on demand, by rubbing sticks together

or banging stones for their sparks. |

|

| |

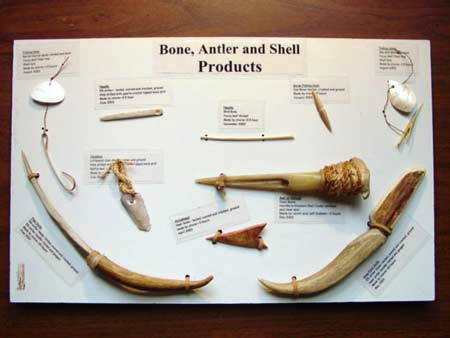

| It’s not my intent to fully teach specific stone age skills in this

article. I do wish to share the benefits of a more primitive and

harmonious lifestyle, one that is allowed to be shaped by the rhythms,

patterns and cycles inherent around us. One way of accomplishing this is

through the adoption and practice of innate (but mostly forgotten)

pre-historic crafts: creating fire, foraging for wild edibles, and

creating simple and effective stone, bone and wood tools. These skills

can be an important asset to those of us who spend a lot of time in the

field, no matter what missions were on.

Salmonberry Flower |

|

| |

| The next time you find yourself on the shore of a creek, river or

ocean, pick up a smooth, oval-shaped cobblestone. Place this rock

(end-wise) upon a larger, stable stone. Take a third rock—your

hammerstone—and strike your cobble forcefully on its upper end. A thin

flake should detach from the parent rock—you’ve just created a discoidal

stone blade, one of humanity’s most ancient cutting tools (2.6 million

year-old stone flakes have been found in Ethiopia). Your new stone knife

will cut grasses, roots, inner barks and leaves for cordage-making, and

meat quite effectively. |

|

| |

I have discovered some of the rewards afforded by a more direct

relationship with nature. Here’s the cause and effects:

Mechanism: Living more lightly within the landscape. If just 1 in 100

people yearned to incorporate primitive skills into her lifestyle, those

in power would feel our positive impact--not only from our reduced

energy consumption, but from our rejection of throw-away consumerism.

Less demand is less production is less pollution.

Internal Benefit: Self Sufficiency. Imagine being able to provide for

your every need—all year ‘round. Needing supplies occasionally, you

travel a short distance to barter with another culture. Hand gestures

and well-timed glances guide the proceedings...you provide these people

with elk antler...they offer obsidian cobbles...everyone leaves content.

No industrial, interstate travel, no fossil fuel expenditure; decrease

in the insect and viral pest migration vectors (namely the export of

poultry and grain around the world). No migration of labor, money,

natural resources, etc. Everything you ever make or do will return to

the earth as it was taken.

Internal Benefit: Freedom. Freedom to go anywhere, anytime, and feel

comfortable that your level of skill will propel you through any

circumstances that arise. Free from worry about food, water, shelter and

warmth. With some knowledge, honed by experience, you know you will be

able to provide yourself with the necessities of life.

External Benefit: Reintegration. Earth is the very matrix of which we

are composed. Can you recall the time when you could understand the

language of nature? We all walk amongst a living calendar, one in which

we participate, if not hesitantly. The raucous territorial cries of the

barred owls usher in the new year. The emergence of salmonberry flowers

informs me that salmon fry are plentiful in the shallow edges of local

creeks. I know it’s time to collect the inner bark of western red cedar

when silver-spotted tiger moth caterpillars are seen grazing upon

hemlock and Douglas fir needles in preparation for their upcoming

transformations. Salt is made in the spring from dried coltsfoot herb.

Medicinal Licorice Fern on Moss-Encrusted Big-Leaf Maple Tree |

|

| |

| There are thousands of primitive skills practitioners here in North

America. You can find these folks through word-of-mouth--we tend to be

known by local boy and girl scout troops, museum curators, classroom

teachers, anthropology professors, and so on. There are very informative

and insightful websites that have comprehensive lists of primitive

skills schools found in Europe, Canada and the U.S. (www.hollowtop.com

is among the best). You can also search for Gatherings (like Winter

Count, Rabbit Stick, Falling Leaves) around the country, which provide

opportunities for you to learn from the masters of the crafts. Solid

ethnographic information on the edible and medicinal uses of plants can

be had by visiting the Plants for a Future database (www.pfaf.org--catalog

of over 7000 species!) and the Native American Ethnobotany Database (herb.umd.umich.edu).

With my back to the opening of this living shelter, I exert increased

downward pressure upon the rotating elderberry shaft. A whisper of smoke

arises from the union of the firesticks, but as any practitioners of

hand drill can attest to, whomever coined the old adage, "where there's

smoke, there's fire" certainly never tried doing this. My daily attempts

to achieve fire with these particular sticks have been fruitless so far.

Nickel-sized blisters on each of my palms challenge me further: In this

case, pain must be accepted in order for me to cook tonight's meal of

Stropharia mushrooms (one of my favorite fungi for the pot). |

|

| |

| With a few more near-desperate turns of the spindle I see a brief

flash of orange-red as the wood powder begins to combust and coalesce

into a coal. Flames will feed and warm me tonight. Such is the

provenance of our symbiotic relationship with elemental fire. |

|

| |

| View this article as a PDF |

|

|

|

|

|

|